The Pattern

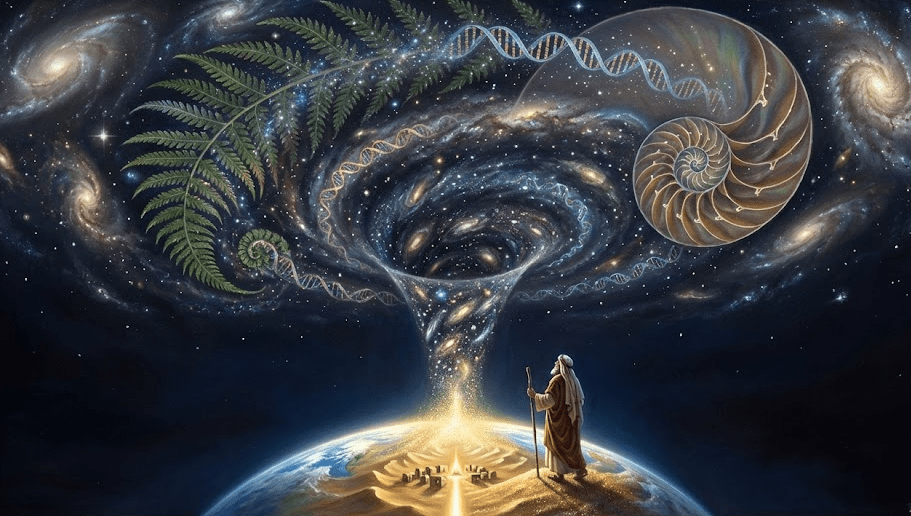

Consider the spiral. It appears everywhere: in the unfurling of a fern, the whorl of a fingerprint, the architecture of a nautilus shell. Galaxies wheel in spirals across unthinkable distances. The double helix of DNA coils at the foundation of every living thing. Water drains in spirals, hurricanes spiral, and the very structure of our inner ear, by which we hear the Word spoken to us, is a spiral. God, it seems, has a pattern, and he is not shy about repeating it.

The Small and the Chosen

The spiral appears in Scripture too, though you have to look with different eyes to see it. It is the shape of God’s attention, the topology of his love: always densest at the hidden center, radiating outward but weighted toward the small. Israel was not selected because it was mighty among nations. Moses reminds the people in Deuteronomy that the Lord set his love upon them not because they were more numerous than other peoples; they were the fewest. David was the youngest son, overlooked even by his own father when Samuel came calling. Mary was hidden in Nazareth, a village so insignificant that Nathanael would later ask whether anything good could come from it. And Christ himself tells us that the Kingdom belongs to the little ones, that to become great we must become as children, that the mysteries are revealed not to the wise and learned but to infants.

This is where the weight falls. The center of gravity in salvation history is never where you would expect it, never at the obvious point of power or prominence. It is always displaced toward the hidden, the overlooked, the least.

The Hidden Village of the Cosmos

Now lift your eyes to the heavens. Our sun is one star among hundreds of billions in the Milky Way. The Milky Way is one galaxy among hundreds of billions of galaxies. The observable universe extends some 93 billion light-years across, and what lies beyond its edges we cannot say. Within this immensity, our planet is less than a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

And yet, the Word became flesh here. On this pale blue dot, the infinite entered finitude. The Creator took on the form of a creature. God became a particular man, in a particular place, at a particular time: a Jewish peasant in Roman-occupied Palestine, born in an animal shelter, raised in obscurity, executed as a criminal. If Israel was chosen among the nations, then Earth has been chosen among the worlds. If Nazareth was the hidden village from which salvation came, then our planet is the hidden village of the cosmos.

The Icon

Here is the mystery worth pondering: God’s selection of Israel is the icon of his selection of Earth.

Not a metaphor, not a parallel, but an icon: a window through which we glimpse the deeper structure of God’s creative and redemptive work. The same love that passed over Egypt and Babylon to rest on a wandering tribe of Semitic nomads is the love that passed over unimaginable expanses of cosmic real estate to take root on this small rocky planet. He loves the particular. He cherishes the small. He hides his glory in dust and ashes, in bread and wine, in water and oil. The God who counts the hairs on our heads and marks the fall of every sparrow is not a God of abstractions but a God of this and here and now. The scandal of particularity, which has always troubled those who want a more universal and reasonable deity, is not a problem to be solved but a revelation to be received. The particular is the doorway to the universal, and the local is the gate to the cosmic.

The Kingdom Within

The spiral does not stop at the planetary or the national. It continues inward. Christ told us that the Kingdom of Heaven is within, and the same topology that governs galaxies and nations governs the geography of the soul. There is a hidden center in you, overlooked perhaps even by yourself, and that is precisely where God wishes to dwell.

The mystics have always known this. The great Carmelite tradition speaks of the interior castle, the deepest chamber of the soul where the King takes up residence. Meister Eckhart spoke of the Seelenfünklein, the spark of the soul where God is eternally born. Augustine found that God was more intimate to him than he was to himself. You are your own Nazareth, your own tiny planet spinning in the darkness. And that is where the weight falls: at the center, at the smallest point, where God has chosen to dwell.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.