Genesis is supposed to be moving. Creation, fall, flood, Babel, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob. The promise line is in motion.

Then the book almost stops.

It parks on Joseph. Chapters and chapters. Detailed scenes. Slow turns. A long family crisis that becomes the backbone of how Israel ends up in Egypt.

So why does Joseph take up so much space?

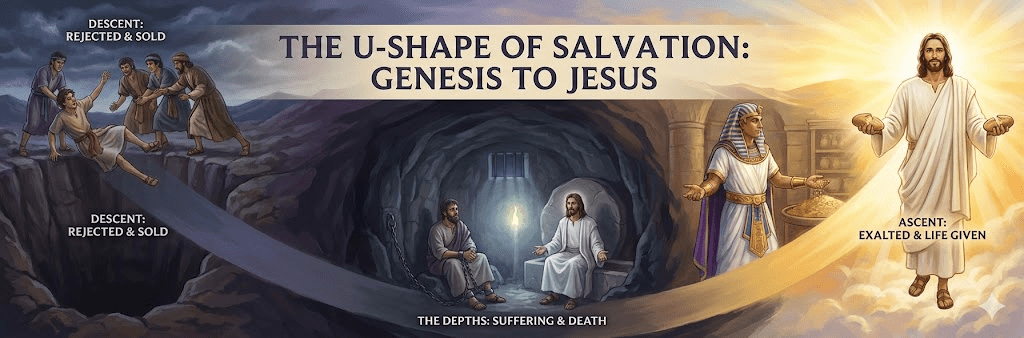

Because he is not only explaining how Israel got to Egypt. He is training you how to read the Bible. He is teaching you the shape of salvation before Jesus arrives. And that shape, when you see it clearly, pushes you toward the patristic way of understanding the cross. The victory, the rescue, the healing, the descent and rising. The whole story as liberation and new life.

Genesis wants you to learn this rhythm early, because it is the rhythm Christ will fulfill.

The story-pattern Genesis wants in your bones

Joseph is the beloved son.

He is rejected by his brothers, Israel. They envy him, hate him, strip him, throw him into a pit, and sell him for silver. They go home and live on top of the lie, while Joseph is carried away like a dead man who still breathes.

Then comes the downward path. Egypt is the land below, the place of exile, the place where you disappear. Joseph becomes a slave. Then he becomes a prisoner. He suffers as an innocent man. The story makes you sit there with him for a long time.

And then God raises him up.

Joseph is lifted to the right hand of the throne. He receives authority over the kingdom. He becomes lord over the storehouses. Bread is placed into his hands.

Then the world starts coming. Nations come to Egypt for life. And eventually his own brothers come too.

They arrive hungry, frightened, and guilty. They do not know who they are standing before. They are face to face with the one they betrayed, and he now has absolute power over their survival.

This is where the story could turn into vengeance.

Instead it turns into revelation, tears, mercy, and reconciliation. Joseph feeds them. He preserves them. He brings them near.

Genesis itself tells you what you are supposed to learn from it:

“You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good… to bring it about that many people should be kept alive.” (Genesis 50:20)

That sentence is the key to the whole mystery.

Real evil happened. The brothers are truly guilty. God does not pretend their sin is fine. And yet God takes the very evil they intended and bends it, without endorsing it, toward the saving of many.

That is the shape.

Why this shape matters when you get to the cross

By the time you reach the New Testament, you should already have categories for what God is doing in Christ. Joseph gives them to you.

Beloved son, rejected by his own. Handed over. Descended into the place below. Humiliated. Then exalted to the throne. Then he becomes life for the world. Then reconciliation.

This is why the Fathers read the cross the way they did.

They did not treat atonement as a puzzle about how God can finally be willing to forgive. They treated it as a rescue mission. Humanity is in bondage, corrupted, and dying. Death is not a metaphor in Scripture. It is an enemy. Sin is not only bad choices. It is a power. The devil is not a cute idea. He is a tyrant, a destroyer, an accuser.

So God comes down into our condition to break it.

Irenaeus talks about Christ recapitulating humanity, redoing the human story from the inside and healing it. Athanasius talks about the Word taking flesh so that, by dying, he might destroy death and restore humanity to life. The Fathers use ransom language at times, and they are not trying to diagram a literal payment to Satan. They are saying something simpler and stronger. The powers seized the innocent one, and that seizure became their downfall.

This is the basic proclamation: Christ entered death and shattered it.

Joseph is the Old Testament practice run for that proclamation.

Jesus as the true Joseph

Jesus is the beloved Son.

He is rejected by his own people. He is handed over. He is sold for silver. He is stripped and shamed. He is treated as cursed. He descends into death itself, the final exile, the real pit.

Then God raises him.

He is exalted as Lord. And what follows is not only a verdict on paper. What follows is life poured out into the world. Bread in his hands. A table set for the starving. Captives released. Sins forgiven. Death losing its claim.

And then comes the part that Joseph trained you for.

Those who betrayed him can still come near.

The risen Christ does not meet his disciples with revenge. He meets them with peace. He restores them. He feeds them. He sends them.

The one wronged becomes the one who saves.

That is Joseph. That is Jesus. Only Jesus is the final version.

The grid this gives you

If you take Joseph seriously, you stop making the cross a narrow mechanism.

You begin to see the cross and resurrection as one act of salvation. The cross is the descent into the enemy’s territory. The resurrection is the victory and the liberation. The ascension is the enthronement. Pentecost is the distribution of life. The church is the rescued people learning to live as a new humanity.

Forgiveness is inside that, and it is precious. Guilt is real. Repentance is real. Judgment is real. But the central drama is bigger than a courtroom scene. It is the defeat of death and the healing of the human race by union with Christ.

That is why the patristic model is not an optional angle. It is the interpretive grid that fits the whole Bible, including Joseph.

Genesis was already teaching you that God saves by turning evil back on itself. God does not become evil to defeat evil. God overrules it, absorbs it, and breaks it.

The brothers meant evil. God meant it for good, so that many would live.

Israel hands over the beloved Son. Evil means it for destruction. God means it for salvation.

The payoff

So the reason Joseph occupies a huge chunk of Genesis is not only because it is a great story.

It is because God wanted to lodge a pattern into you.

Descent. Exile. Suffering. Silence. Then exaltation. Then bread for the world. Then reconciliation.

Once you see that, the gospels stop feeling like a new religion dropped out of the sky. They feel like the climax of a story you have already been reading.

And the right response is not to walk away impressed with a clever connection.

It is to look at Christ and adore him.

Because the God who wrote Joseph’s story has done it in history, for real, for the whole world.

He went down to bring us up.

He entered the grave to make the grave a passage.

He took what was meant for evil and made it the place where life is stored.

That is the mystery Genesis sets up.

And Joseph is how it pays it off, before you ever reach Bethlehem.